lunes, 26 de octubre de 2009

Direct Cinema

This is a style of film-making that is often confusing and difficult to define. While it has some similarities to Cinema Verité and Free Cinema, it is unique to North America. It is different from traditional documentaries for many different reason. Most noticeably the

"events seem recorded exactly as they happen without rehearsal and with minimal editing."

Unlike the traditional documentary's use of a voiceover and interviewer, in direct cinema

"people are allowed to speak without guidance or interruption, inadvertently revealing their own motives, attitudes and psychology."

How Did Direct Cinema Get Here?

Direct Cinema developed in the 1950s and 1960s in North America. It was the result of both sociological and practical changes to the world of film making. Equipment that was developed for television news documentary, such as better film stock that could be used in natural lighting, directional microphones, and a zoom lens, was used in order to

"get closer to a subject without interfering in the natural flow of speech or action."

The most obvious use of the Direct Cinema technique would be for documentaries, but they were also used in many fiction films. Films like A Married Couple took footage shot during the daily lives of people, and then edited it together to create a fictional piece. Thus, Direct Cinema is not pure documentary; due to the style of shooting and the use of "real" people and events it is not true fiction either. In many ways it mixes the two.

How Is Direct Cinema Different From Cinema Verité?

Often these two styles of film-making are confused. Many people think that they are the same style. The most obvious difference is that Direct Cinema insisted that the

"subjects (become) so involved with what they are doing that they forget the presence of the camera and the film-maker."

Whereas Cinema Verité felt that the camera made the subject

"aware of themselves by giving them a feeling of importance".

Elsewhere on the web, see Cinema Verite: Defining the Moment, from the National Film Board.

Critiques of Direct Cinema?

Perhaps the most obvious problem with Direct Cinema is that it often could "seem amateurish" and had a "home movie quality". However, this limitation also "adds to the authenticity" of the experience of watching a Direct Cinema film. One of the most difficult parts of watching a Direct Cinema film is to avoid judging it by the same standards and expectations with which one would judge a traditional documentary or dramatic film. Direct Cinema was trying to re-define what films were used for and how films would be seen.

What Happened to Direct Cinema?

Direct Cinema in a pure form didn't last very long. Some critics believed that Direct Cinema would replace both drama and traditional forms of documentary. Instead, parts of it were quickly adopted by the very styles of film making it was going to replace, and can be seen in films and television today.

© 1998 Hannah Rasmussen

Chantel Ackerman:Moving Through Time And Space

Recognized as one of the most important directors in film history, Belgian filmmaker Chantal Akerman presents her key films and major installations, spotlighting the crossover genres of film and visual art. The five projects of this touring exhibition, including a newly commissioned film, span more than two decades of Akerman’s career, opening a window on to the shifting frames between fact and fiction. Exploring the politics of territorial borders, recent histories of racism, and the poetics of personal journeys, Akerman’s films touch on ideas about image, gaze, space, performance, and narration.

Recognized as one of the most important directors in film history, Belgian filmmaker Chantal Akerman presents her key films and major installations, spotlighting the crossover genres of film and visual art. The five projects of this touring exhibition, including a newly commissioned film, span more than two decades of Akerman’s career, opening a window on to the shifting frames between fact and fiction. Exploring the politics of territorial borders, recent histories of racism, and the poetics of personal journeys, Akerman’s films touch on ideas about image, gaze, space, performance, and narration.

Chantal Akerman: Moving Through Time and Space is a collaborative effort of four institutions: Blaffer Gallery, the Art Museum of the University of Houston; the MIT List Visual Arts Center, Cambridge; Miami Art Museum (a MAC@MAM presentation); and the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis.

The exhibition and catalog have been generously supported by The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts and Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation (CIFO). Additional support for the catalog has been provided by the Barbara Lee Family Foundation Fund at the Boston Foundation.

General support for the Contemporary’s exhibitions program is generously provided by the Whitaker Foundation; The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts; William E. Weiss Foundation; Nancy Reynolds and Dwyer Brown; Regional Arts Commission; Missouri Arts Council, a state agency; Arts and Education Council; and members of the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis.

Georges Franju Sangre De Las Bestias

Screening Georges Franju’s Blood of the Beasts in a class focusing on Marxist theory somewhat demands a Marxist reading of the film. But fairness will be attempted.

Blood of the Beasts is much less a vegetarian propaganda film and much more a look at an industry disconnected from the society which and into which it feeds. Franju’s dissonance between the rather happy, but nevertheless postwar, life of sub/urban Paris is signified through a change in the voice of narration (from female to male), an abrupt shift/absence of music, and a transition from long shots to medium shots. Then, of course, there is the change in content. Another thing Franju doesn’t seem to be saying is that the work done in slaughterhouses is necessarily wrong. On the contrary, the animals are killed with utmost efficiency and (apparently) painlessness. The worst any of them undergoes is briefly getting pushed around prior to decapitation (which, I hear, is a pain-free experience).

Granted, watching these things on film (even if it is black and white) feels traumatic to one who is not accustomed to such sights. But whether this was Franju’s intent, it certainly attests to the point that there is a real disjoint between daily life, with all of its burgers and steaks, and the place where animals begin the transition to becoming burgers and steaks. In an interview, Franju firsthand confirms what the style of his film already told us: he went to pains to ensure that the film was a work of art. This was his chief goal. He insists that we wasn’t particularly interested in the subject of slaughterhouses, but he was intrigued by the provocative presence of a moat separating the slaughterhouse from the rest of the city. When some said that color photography would have enhanced Blood of the Beasts‘ effect on viewers, Franju insisted that color would have removed the art from the film and reduced it to shock-value. And while shock-value wasn’t Franju’s intent, clearly he was attempting to evoke an often emotional response from the viewer both through content and style. He did not position his camera, say, behind the horse as it was being slaughtered (“shot” in the head), only to show us the animal dropping to the ground. Rather, the camera is right on front to show the entire picture.

The presence, in particular, of the former French boxing champion employed at the slaughterhouse seemed intentionally drawn out by Franju. To be sure, he wasn’t the only worker to be mentioned, but Franju must have know that his background would be more interesting than the rest and therefore made a point of it. Is it too simplistic to wonder if the boxer isn’t another means of disassociating the slaughterhouse from a “normal” Parisian life? Sure, lots of people love boxing. But not many people actually box. Franju could be noticing a connection between two professions: one that is paid to beat on humans, another to kill animals.

The nuns are more interesting and seem to serve the film’s purpose better. Mostly shot from behind, they are identified in terms of their spiritual calling rather than as individuals per se. The nuns cross the boundary of the moat separating the slaughterhouse much in the same way as they would cross the line into diseased territory to witness to the sick and poor. They visit the slaughterhouse in order to obtain fat, an undesirable part of the animals that would otherwise presumably be discarded. Nuns have seemingly always been those that society sends to places it would otherwise prefer not to visit. Their presence at the slaughterhouse hammers home the point that this is a place that is truly “other” from the world to which it belongs. The fracture between production and consumption is a Marxist lament, and one that isn’t without merit. In (Marxist) theory, knowledge at least and participation at best would positively affect the exchange value of such commodities as these. Knowing the interior of a slaughterhouse would certainly cause some to abstain from meat, and perhaps it would cause others to appreciate a little better the nature and history behind a good steak.

Night Mail De Basil Wright

Basil Wright was the first recruit to join John Grierson at the Empire Marketing Board's film unit in 1930, shortly after he graduated from Cambridge University. Wright's 1934 film Song of Ceylon is his most celebrated work. Shot on location in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) the film was completed with the composer Walter Leigh at the GPO Film Unit in London. At the GPO, Wright acted as producer and wrote the script for Night Mail (1936) for which he received a joint directorial credit with Harry Watt. Wright had introduced his friend W. H. Auden to the film unit and the poet’s verse was included in the film.

Wright left the GPO to form his own production company, The Realist Film Unit (RFU). There he directed Children at School with money from the Gas Industry and The Face of Scotlandfor The Films of Scotland Committee.

During World War II, Wright worked only as a producer, first at John Grierson's Film Centre before joining The Crown Film Unit between 1945 and 1946 as producer-in-charge. Among the best known films he produced for Crown are Humphrey Jennings' A Diary for Timothy (1946) and A Defeated People (1946). Returning to direction in the early 1950s, his films includedWaters of Time (1951) made for the Festival of Britain, World Without End (1953) directed with Paul Rotha for UNESCO and Greece: The Immortal Land (1958) in collaboration with his friend the artist Michael Ayrton.

Writing throughout the 30s and 40s, Basil Wright had contributed to the theoretical development of documentary in the movement’s journals Cinema Quarterly, World Film News andDocumentary Newsletter. He was the film critic for The Spectator after Graham Greene left. Wright was a regular contributor to the British Film Institute’s Sight and Sound during the 1940s and '50s. He published a small book: The Uses of Film (1948) and his personal (extensive) history of cinema The Long View (1974). He taught at the University of Southern California (1962 and 1968), The National Film and Television School in London (1971-73) and Temple University in Phipadelphia (1977-78). He was Governor of the British Film Institute, a fellow of theBritish Film Academy and President of the International Association of Documentary Filmmakers.

In his films Wright combined an ability to look closely and carefully at a subject with a poetic and often experimental approach to editing and sound. In Britain he is commemorated with a film prize awarded biennially by the Royal Anthropological Institute.

Night Mail is a 1936 documentary film about a London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS) mail train from London to Scotland, produced by the GPO Film Unit. A poem by English poet W. H. Auden was specially written for it, used in the closing few minutes, as was music byBenjamin Britten. (The two men also collaborated on a rail-documentary on the line from London to Portsmouth, The Way to the Sea, also in 1936.) The film was directed by Harry Watt and Basil Wright, and narrated by John Grierson and Stuart Legg. The Brazilian filmmaker Alberto Cavalcanti was the sound director. It starred Royal Scot 6115 Scots Guardsman.[citation needed]

As recited in the film, the poem's rhythm imitates that of the train's wheels as they clatter over the track sections, beginning slowly but picking up speed so that by the time the narration reaches the penultimate verse the narrator is speaking at a breathless pace. As the train slows toward its destination the final verse is taken at a more sedate pace.[1][improper synthesis?] The famous opening lines of the poem are "This is the Night Mail crossing the border / Bringing the cheque and the postal order". The poem however remains under copyright.[2]

Such is the iconic status of the film, it was used as inspiration for a famous British Rail advertisement of the 1980s, known as the "concerto ad".

Nuclear holocaust refers to the possibility of nearly complete annihilation of human civilization by

nuclear warfare. Under such a scenario, all or most of the Earth is made uninhabitable by nuclear weapons in future world wars.

A common definition of the word "holocaust": "great destruction resulting in the extensive loss of life,

especially by fire."[1] The word is derived from theGreek term "holokaustos" meaning "completely burnt." Po

ssibly the first printed use of the word "holocaust" to describe an imagined nuclear destruction is Regi

nald Glossop's 1926: "Moscow ... beneath them ... a crash like a crack of Doom! The echoes of this Holocaust rumbled and rolled ... a distinct

smell of sulphur ... atomic destruction."

[2] In the 1960s the principal referent of the unmodified "holocaust" was nuclear destruction.[3] Since the mid 1970s the capitalized term "Holocaust" has been closely associated with the Nazi mass slaughter of Jews (see Holocaust) and "holocaust" in its nuclear destruction sense is almost always preceded by "atomic" or "nuclear".[4]

Nuclear physicists and authors have speculated that nuclear holocaust could result in an end to human life, or at

least to modern civilization on Earth due to the immediate effects of nuclear fallout, the loss of much modern technology due to electromagnetic pulses, or nuclear winter and resulting extinctions.

Nuclear warfare, or atomic warfare, is a military conflict or political strategy in which nuclear weapons are

used. Compared to conventional warfare, nuclear warfare is vastly more destructive in range and extent of damage. A major nuclear exchange could have severe long-term effects, primarily from radiation release but also

from possible atmospheric pollution leading to nuclear winter, that could last for decades, centuries, or even millennia after th

e initial attack.[1][2] Nuclear war is considered to

bear existential risk for civilization on Earth.[3][4]

The first, and to date only, nuclear war was the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan by the United States shortly before the end of World War II.[5][6]At the time of those bombings, the United

States was the only country to possess atomic weapons. After World War II, nuclear weapons were also developed by theUnited Kingdom, France, the Soviet Union, and the People's Republic of China, which contributed to the state of conflict and tension that became known as theCold War. In the 1970s, India and 1990s, Pakistan, countries openly hostile to each other, developed nuclear weapons.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the resultant end of the Cold War, the threat of a major nuclear wa

r between the superpowers was generally thought to have receded. Since then, concern over nuclear weapons has

shifted to the prevention of localized nuclear conflicts resulting from nuclear proliferation, and the threat of

The Doomsday Clock is a symbolic clock face, maintained since 1947 by the board of directors of the

Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists at the University of Chicago, that uses the analogy of the human species being at a

time that is "minutes to midnight", wherein midnight represents "catastrophic destruction". Originally, the analogy represented the threat of global nuclear war, but since includes climate-

changing technologies and "new developments in the life sciences and nanotechnology tha

t could inflict irrevocable harm".[1] The closer the clock is to midnight, the closer the world is estimated to be to global disaster.

Since its inception, the clock has appeared on every cover of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Its first representation was in 1947, when magazine co-founder Hyman Goldsmith asked artist Martyl Langsdorf (wife of

Manhattan Project physicist Alexander Langsdorf, Jr.) to design a cover for the magazine's June 1947 issue.

The number of minutes before midnight – measuring the degree of nuclear, environmental, and technological threats to mankind – is periodically corrected; currently, the clock reads five minutes to midnight, having advanced two minutes on 17 January 2007.

Human Remains De Jay Rossenblatt

Human Remains by Rhys Graham

Human Remains is an acclaimed short film by psychologist turned filmmaker, Jay Rosenblatt. In much of his work, Rosenblatt lyrically weaves together documentary, narrative and avant-garde techniques to deal with elements of human psychology. Usually working alone or in collaboration with Jennifer Frame, Rosenblatt adopts a minimal, independent approach to his film practice, with an insightful intelligence that distinguishes each undertaking. His body of work is characterised by the experimental tradition of working with the familiar - particularly found footage and cinematic or archival remnants - to reveal or create layers of meaning. In this sense, his work can be compared to artists such as Matthias Müller, Martin Arnold and Jackie Farkas. In The Smell of Burning Ants (1994), for example, Rosenblatt uses recontextualised footage and staged scenes to examine the ways that modes of masculinity are initiated in the cruel interactions of young boys. In the recent King of the Jews (2000) he uses cinematic and televisual portrayals of Jesus Christ to investigate anti-Semitism in Christian cultures, and to present a personal insight into fear, guilt and forgiveness. In Human Remains, Rosenblatt departs from Hannah Arendt's notion of 'the banality of evil' and explores, with occasional wit and the mournfulness of recalled suffering, that it is this banality that makes it impossible for us to distance evil from everyday life. Hitler, along with four of the world's most infamous dictators, Mao Tse Tung, Josef Stalin, Benito Mussolini and Francisco Franco, become the objects of an incisive study that suggests that even the most monstrous of men are made common by banal human activities. Rosenblatt's shared knowledge of their eating habits, sleeping patterns, likes, dislikes, and unrealised ambitions, recall these historical figures from the other-ness of 'evil' and bring them close, too close, under our skin, to a place where the sheer fact of their humanity confronts and challenges our understanding of these horrific histories. Over a period of eight months of research, Rosenblatt mined biographical sources of the men for clues and information on their private lives. What results is a revelation of the most intimate details. Through fictional scripted narrations, we learn the minutiae of the private everyday life of each man in turn. Importantly, the filmmaker avoids any reference to the events that made these men figures of terror, cleverly imbuing the mundanity of their recitation with an intensity of meaning. When Hitler confesses, "some thought I was quite a lady-killer", or "I had difficulty making even the tiniest decisions" our awareness of the past make these trivial comments both wry and chilling. A similar slippage of meaning occurs when Mao, talking of his favourite dish of bitter melon reflects, "everyone should taste some bitterness in their life", or Stalin reveals, "I had a good sense of humour", or Franco restates his own dying words, "How hard it is to die." This occasionally brutal irony appears most transparently when Rosenblatt juxtaposes Mussolini pronouncing, "when willing, the Italian people can do anything", with a slow pulsing image of the corpses of Mussolini's victims. This is one of the few, brief glimmers of the things we already know of these men. The performed voice-overs occur on two simultaneous levels: firstly, in an acted narration in the original language of each man; secondly, in a translated monologue which speaks over, but does not obscure the first voice. It creates the sound of a chorus, as well as the carefully chosen words of confession. This device implies a constructed 'authenticity' by suggesting that the words spoken are that of the actual dictator, gently confiding in us, translated by the filmmaker after the fact. At the same time, this layering of meaning is what is most important to Rosenblatt. Each brief revelation is meaningful because of the additional complex layers that the audience brings to the film. In this way, Rosenblatt is exemplary. The viewer of his work is always active. Stitching together meaning for themselves, making the investigation their own. There is also a somewhat elusive technique at work in Human Remains that arises from Rosenblatt's use of the technique of optical printing. For many, the archival clips of these figures are familiar visual remnants from an unimaginably horrific past. Over time, these fragments have metonymically come to represent a knowledge of each dictator: we 'know' Stalin through his visage, Hitler through his carriage and stance, and Mao through his wardrobe. At one historical remove, Rosenblatt deals directly with these artifacts, reconfiguring them from a distanced and therefore 'safe' understanding into an intimate and challenging knowledge of these men and their actions. This rupture in known history, created by the act of reprinting the images, changing the spatial and temporal configurations of each shot, creates a reflective space between the archival remnant and the filmmaker's intention. It is in this space that Rosenblatt labours, finding subtle ways to investigate psychic undercurrents that may have gone undetected. In this space he seeks to create a new way of seeing, while also reinforcing the audience's awareness of the act of cinematic engagement as a potent space for reflection and criticism. Though disturbing in its content, Human Remains is frequently graceful and poetic. Rosenblatt's meditation on the minute gestures and glances of the dictators makes for compelling viewing. In slow-motion sequences, Rosenblatt shows Stalin examining the sweat he has wiped from his brow or Mussolini turning to gaze directly into the camera. The latter image is the strongest of all. At different points in the film, each of the men turns to the camera and locks gazes with the audience, if only for a moment. This, combined with the intimate narratives invokes a highly personal engagement between the viewer and the film. We are invited to examine their bodies and faces, their movements, smiles and habitual actions in a way that is devotional if not fetishistic. Rosenblatt, through all this, assumes the viewers knowledge of recent history. For, of course, he is not examining these men with the eye of the seduced camera. Rather, he uses intimacy as a way to rupture the emotional gap that a world-weary audience might project onto this subject matter. His approach reminds us that we can't linger this close to evil without daring to look it in the eye and ask ourselves, deeply, what it is that we see. In this way, Human Remains creates a new strategy for the discussion of 20th century dictators. Arendt introduced the notion that investigating those responsible for horrendous crimes against humanity led to "a lesson that this long course in human wickedness had taught us - the lesson of the fearsome, word-and-thought-defying banality of evil" (2). At the beginning of a new century we have taken for granted that this evil occurs. What Rosenblatt reminds us, in a most uncomfortable manner, is that these men are not monsters, and therefore are not able to be distanced from everyday human interaction. They are men, full of foibles, failings and absurd obsessions who are also capable of committing the most monstrous of crimes and implementing the most inhumane of regimes. Human Remains challenges us to ask how could a man who seemed inordinately preoccupied with his bowels and dietary habits also initiate the systematic murders of millions. Or how could another man, unable to muster the energy to get out of his bed, or to clean himself, eradicate the culture and society of the world's largest populace. Rosenblatt's extraordinary insights are often as psychologically revealing or comic as they are mundane. Hitler and Mao had only one testicle. Franco was an aspiring filmmaker. Mao never bathed ("My genitals were washed inside the bodies of my women") and brushed his teeth with green tea ("a tiger never brushes his teeth"). Yet it is the broader context, examining men we know to have violently changed the face of the world, that makes the simple details so chilling. In an interview, referring to the parallels between a previous career as a mental health counsellor and his work as a filmmaker, Rosenblatt suggested that his approaches are always "to confront people on a subliminal level with things which they would prefer avoid". (3) In this journey into the dark hearts of humankind, two recurring images are used by Rosenblatt to link each sequence: a dark, dimly perceived image of a gravedigger overturning soil in a graveyard, and the repetitive clatter of a train riding along the rails. It is these images that prepare us to journey forth and dig deep into an archive of historical visual artefacts, some familiar, some not so, which will overturn corpses and remains that do not rest in peace in our collective memory. |

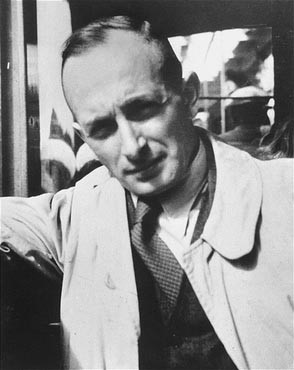

Biografia de Eichmann

Karl Adolf Eichmann (1906-1962) headed Gestapo Department IV B4 for Jewish Affairs, serving as a self proclaimed 'Jewish specialist' and was the man responsible for keeping the trains rolling from all over Europe to death camps during the Final Solution.

Eichmann was born on March 19, 1906 near Cologne, Germany, into a middle class Protestant family. His family moved to Austria following the death of young Adolf''s mother. He spent his youth in Linz, Austria, which had also been Hitler's home town. As a boy, Eichmann was teased about his looks and dark complexion and was nicknamed "the little Jew" by classmates.

After failing to complete his engineering studies, Eichmann had various jobs including working as a laborer in his father's small mining company, working in sales for an electrical construction company and also worked as a travelling salesman for an American oil company.

In 1932 at age 26 he joined the growing Austrian Nazi Party at the suggestion of his friend Ernst Kaltenbrunner. Eichmann then became a member of the SS and in 1934 served as an SS corporal at Dachau concentration camp. In September 1934 Eichmann found relief from the monotony of that assignment by getting a job in Heydrich's SD, the powerful SS security service.

Eichmann started out as a filing clerk cataloging information about Freemasons. He was then assigned to the Jewish section which was busy collecting information on all prominent Jews. This marked the beginning of Eichmann's interest in the Jews.

He studied all aspects of Jewish culture, attended Jewish meetings and often visited Jewish sections of cities while taking volumes of notes. He became familiar with the issue of Zionism, studied Hebrew and could even speak a bit of Yiddish. He gradually became the acknowledged 'Jewish specialist,' realizing this could have positive implications for his career in the SS.

He soon attracted the attention of Heydrich and SS Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler who appointed Eichmann to head a newly created SD Scientific Museum of Jewish Affairs.

Eichmann was then assigned to investigate possible "solutions to the Jewish question." He visited Palestine in 1937 to discuss the possibility of large scale immigration of Jews to the Middle East with Arab leaders. British authorities, however, ordered him out of the country.

With the Nazi takeover of Austria in March of 1938, Eichmann was sent to Vienna where he established a Central Office for Jewish Emigration. This office had the sole authority to issue permits to Jews desperately wanting to leave Austria and became engaged in extorting wealth in return for safe passage. Nearly a hundred thousand Austrian Jews managed to leave with most turning over all their worldly possessions to Eichmann's office, a concept so successful that similar offices were established in Prague and Berlin.

In 1939 Eichmann returned to Berlin where he was appointed the head of Gestapo Section IV B4 of the new Reich Main Security Office (RSHA). He was now responsible for implementation of Nazi policy toward the Jews in Germany and all occupied territories (eventually totaling 16 countries). Eichmann thus became one of the most powerful men in the Third Reich and would remain head of IV B4 for the remainder of the Reich.

In July 1940 Eichmann presented his Madagascar Plan proposing to deport European Jews to the island of Madagascar, off the coast of east Africa. The plan was never implemented.

Following the start of World War Two and the occupation of Poland and the Soviet Union, SS Einsatz groups murdered members of the aristocracy, professionals, clergy, political commissars, suspected saboteurs, Jewish males and anyone deemed a security threat.

In Poland, which had the largest Jewish population in Europe (3.35 million) Heydrich and Eichmann ordered the Jews to be rounded up and forced into ghettos and labor camps. Inside ghettos such as Warsaw, large numbers of Jews were deliberately confined in very small areas, resulting in overcrowding and death through disease and starvation.

The ghettos were chosen based on their proximity to railway junctions, pending the future "final goal" regarding the Jews. The Nazis also ordered the establishment of Jewish administrative councils within the ghettos to implement Nazi policies and decrees.

"The Führer has ordered the physical extermination of the Jews," Heydrich told Eichmann, who later reported this statement during his trial after the war.

Under the supervision of Eichmann, SS Einsatz groups in occupied areas of the Soviet Union now turned their full attention to the mass murder of Jews. Einsatz leaders kept highly detailed, daily records. Competitions even arose among the four main groups as to who posted the highest numbers. In the first year of the Nazi occupation of Soviet territory, over 300,000 Jews were murdered.

The methods used at this time involved gathering Jews to a secluded location and then shooting and burying them. At his trial in Nuremberg after the war, Otto Ohlendorf, commander of Einsatzgruppe D, described the method...

"The unit selected would enter a village or city and order the prominent Jewish citizens to call together all Jews for the purpose of resettlement. They were requested to hand over their valuables and shortly before execution, to surrender their outer clothing. The men, women, and children were led to a place of execution, which in most cases was located next to a more deeply excavated antitank ditch. Then they were shot, kneeling or standing, and the corpses thrown into the ditch."

Eichmann travelled to Minsk and witnessed Jews being killed in this manner. He then drove to Lvov where a mass execution had just occurred. During his trial after the war, Eichmann described the scene. The execution ditch had been covered over with dirt, but blood was gushing out of the ground "like a geyser" due to pressure from the bodily gasses of the deceased.

SS Reichsführer Himmler also witnessed such a killing and nearly fainted. He then ordered more 'humane' methods to be found, mostly to spare his SS men the ordeal of such direct methods. The Nazis then turned their attention to gassing which had already begun on a limited scale during the euthanasia program.

Mobile gas-vans were used at first. These trucks had sealed rear compartments into which the engine fumes were fed, causing death via carbon monoxide.

On July 31, 1941 Heydrich was told by Göring to prepare "a general plan of the administrative material and financial measures necessary for carrying out the desired Final Solution of the Jewish question."

In January 1942 Eichmann helped Heydrich organize the Wannsee Conference in Berlin during which Heydrich and Eichmann along with 15 Nazi bureaucrats planned the extermination of the entire Jewish population of Europe and the Soviet Union, estimated at 11 million persons.

"Europe would be combed of Jews from east to west," Heydrich bluntly stated.

Obersturmbannführer (Lt. Col.) Eichmann's sole purpose now became issues related to the Final Solution. He assumed the leading role in coordinating the deportation of Jews from every corner of Europe to existing ghettos in occupied Poland and to newly constructed gas chambers at places such as Sobibor, Chelmno, Treblinka and Auschwitz-Birkenau. At Birkenau the gas chamber disguised as a shower room could accommodate 2000 persons at a time.

"The way we selected our victims was as follows," Auschwitz Kommandant Höss reported after the war: "We had two SS doctors on duty at Auschwitz to examine the incoming transports of prisoners. The prisoners would be marched by one of the doctors who would make spot decisions as they walked by. Those who were fit for work were sent into the camp. Others were sent immediately to the extermination plants. Children of tender years were invariably exterminated since by reason of their youth they were unable to work."

Eichmann took a keen interest in Auschwitz from its founding and visited there on numerous occasions. He helped Höss select the site for the gas chambers, approved the use of Zyklon-B, and witnessed the extermination process.

At the death camps, all belongings were taken from Jews and processed. Wedding rings, eye glasses, shoes, gold fillings, clothing and even hair shaven from women served to enrich the SS, with the proceeds funneled into secret Reichsbank accounts.

With boundless enthusiasm for his task and fanatical efficiency, Eichmann travelled throughout the Reich coordinating the Final Solution, insuring a steady supply of trainloads of Jews to the killing centers of occupied Poland where the numbers tallied into the millions as the war in Europe dragged on.

In March of 1944 Germany occupied its former satellite Hungary which had the last big Jewish population (725,000) in Europe. On that same day, Eichmann arrived with Gestapo "Special Section Commandos."

By mid May, deportations of Jews from Hungary to Auschwitz began. Eichmann then travelled to Auschwitz to personally oversee and speed up the extermination process. By the end of June, 381,661 persons - half of the Jews in Hungary - arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau, which went on to record its highest-ever daily numbers of persons gassed and burned.

In August 1944 Eichmann reported to Himmler that approximately 4 million Jews had died in death camps and that an estimated 2 million had been killed by mobile units.

By the end of 1944, the Allies were closing in on Hitler's Reich from all sides. As the Soviet Army approached Budapest, Hungary, Himmler ordered Eichmann to cease deportations. However Eichmann ignored this and had another 50,000 Hungarian Jews rounded up and forced on an eight day death march to Austria.

Following the surrender of Nazi Germany in May of 1945, Eichmann was arrested and confined to an American internment camp but managed to escape because his name was not yet well known. In 1950, with the help of the SS underground, he fled to Argentina and lived under the assumed name of Ricardo Klement for ten years until Israeli Mossad agents abducted him on May 11, 1960.

Eichmann went on trial in Jerusalem for crimes against the Jewish people, crimes against humanity and war crimes. During the four months of the trial over 100 witnesses testified against him. Eichmann took the stand and used the defense that he was just obeying orders. "Why me," he asked. "Why not the local policemen, thousands of them? They would have been shot if they had refused to round up the Jews for the death camps. Why not hang them for not wanting to be shot? Why me? Everybody killed the Jews."

He was found guilty on all counts, sentenced to death and hanged at Ramleh Prison, May 31, 1962.

A fellow Nazi reported Eichmann once said "he would leap laughing into the grave because the feeling that he had five million people on his conscience would be for him a source of extraordinary satisfaction."

Copyright © 1997 The History Place™ All Rights Reserved